Resurrectionists In The United Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Resurrectionists were

Resurrectionists were

In London, late 18th-century anatomists may have delegated their grave-robbing almost entirely to body snatchers, or, as they were commonly known, resurrectionists. A fifteen-strong gang of such men, exposed in Lambeth in 1795, supplied "eight surgeons of public repute, and a man who calls himself an Articulator". The report into their activities lists a price of two

In London, late 18th-century anatomists may have delegated their grave-robbing almost entirely to body snatchers, or, as they were commonly known, resurrectionists. A fifteen-strong gang of such men, exposed in Lambeth in 1795, supplied "eight surgeons of public repute, and a man who calls himself an Articulator". The report into their activities lists a price of two

Resurrectionists usually found corpses through a network of informers. Sextons, gravediggers, undertakers, local officials; each connived to take a cut of the proceeds. Working mostly in small gangs at night with a "dark lanthorn", their ''

Resurrectionists usually found corpses through a network of informers. Sextons, gravediggers, undertakers, local officials; each connived to take a cut of the proceeds. Working mostly in small gangs at night with a "dark lanthorn", their ''

As many as seven gangs of resurrectionists may have been at work in 1831. The 1828 Select Committee on Anatomy believed that there were about 200 London resurrectionists, most of them working part-time. The London Borough Gang, which operated from about 1802 to 1825, at its peak consisted of at least six men, led first by a former hospital porter named Ben Crouch, and later by a man called Patrick Murphy. Under the protection of Astley Cooper, Crouch's gang supplied some of London's biggest anatomical schools, but relations were not always amicable. In 1816 the gang cut off supplies to the St Thomas Hospital School, demanding an increase of two guineas per corpse. When the school responded by using freelancers, members of the gang burst into the dissecting rooms, threatened the students and attacked the corpses. The police were called, but worried about adverse publicity, the school paid their attackers' bail and opened negotiations. The gang also attempted to put rivals out of business, sometimes by desecrating a graveyard (thereby rendering it unsafe to rob graves from for weeks thereafter) and other times by reporting freelance resurrectionists to the police, recruiting them once freed from prison. Joshua Naples, who wrote ''The Diary of a Resurrectionist'', a list of his activities from 1811–1812, was one such individual. Among entries detailing the graveyards he plundered, the institutions he delivered to, how much he was paid and his drunkenness, Naples diary mentions his gang's inability to work under a full Moon, being unable to sell a body deemed "putrid", and leaving a body thought to be infected with

As many as seven gangs of resurrectionists may have been at work in 1831. The 1828 Select Committee on Anatomy believed that there were about 200 London resurrectionists, most of them working part-time. The London Borough Gang, which operated from about 1802 to 1825, at its peak consisted of at least six men, led first by a former hospital porter named Ben Crouch, and later by a man called Patrick Murphy. Under the protection of Astley Cooper, Crouch's gang supplied some of London's biggest anatomical schools, but relations were not always amicable. In 1816 the gang cut off supplies to the St Thomas Hospital School, demanding an increase of two guineas per corpse. When the school responded by using freelancers, members of the gang burst into the dissecting rooms, threatened the students and attacked the corpses. The police were called, but worried about adverse publicity, the school paid their attackers' bail and opened negotiations. The gang also attempted to put rivals out of business, sometimes by desecrating a graveyard (thereby rendering it unsafe to rob graves from for weeks thereafter) and other times by reporting freelance resurrectionists to the police, recruiting them once freed from prison. Joshua Naples, who wrote ''The Diary of a Resurrectionist'', a list of his activities from 1811–1812, was one such individual. Among entries detailing the graveyards he plundered, the institutions he delivered to, how much he was paid and his drunkenness, Naples diary mentions his gang's inability to work under a full Moon, being unable to sell a body deemed "putrid", and leaving a body thought to be infected with

The moving in 1783 of London's executions, from

The moving in 1783 of London's executions, from

In March 1828, in

In March 1828, in

Resurrectionists were

Resurrectionists were body snatcher

Body snatching is the illicit removal of corpses from graves, morgues, and other burial sites. Body snatching is distinct from the act of grave robbery as grave robbing does not explicitly involve the removal of the corpse, but rather theft fro ...

s who were commonly employed by anatomists in the United Kingdom during the 18th and 19th centuries to exhume

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

the bodies of the recently dead. Between 1506 and 1752 only a very few cadaver

A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body that is used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Stud ...

s were available each year for anatomical research. The supply was increased when, in an attempt to intensify the deterrent effect of the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

, Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

passed the By allowing judges to substitute the public display of executed criminals with dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

(a fate generally viewed with horror), the new law significantly increased the number of bodies anatomists could legally access. This proved insufficient to meet the needs of the hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emerge ...

s and teaching centres that opened during the 18th century. Corpses and their component parts became a commodity, but although the practice of disinterment was hated by the general public, bodies were not legally anyone's property. The resurrectionists therefore operated in a legal grey area

Grey area or gray area may refer to a fuzzy border between two states, such as legal and illegal actions. It may also refer to:

* ''Grey Area'' (album), a 2019 album by Little Simz

* Grey Area (gallery), an art project in Paris

* ''Grey Area'' ...

.

Nevertheless, resurrectionists caught plying their trade ran the risk of physical attack. Measures taken to stop them included the use of increased security at graveyards. Night watches patrolled grave sites, the rich placed their dead in secure coffin

A coffin is a funerary box used for viewing or keeping a corpse, either for burial or cremation.

Sometimes referred to as a casket, any box in which the dead are buried is a coffin, and while a casket was originally regarded as a box for jewel ...

s, and physical barriers such as mortsafe

A mortsafe or mortcage was a construction designed to protect graves from disturbance and used in the United Kingdom. Resurrectionists and Night Doctors had supplied schools of anatomy since the early 18th century. This was due to the necessity ...

s and heavy stone slabs made extraction of corpses more difficult. Body snatchers were not the only people to come under attack; in the public's view, the 1752 Act made anatomists agents of the law, enforcers of the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. Riots at execution sites, from where anatomists collected legal corpses, were commonplace.

Matters came to a head following the Burke and Hare murders

The Burke and Hare murders were a series of sixteen killings committed over a period of about ten months in 1828 in Edinburgh, Scotland. They were undertaken by William Burke and William Hare, who sold the corpses to Robert Knox for dissectio ...

of 1828. Parliament responded by setting up the 1828 Select Committee Select committee may refer to:

*Select committee (parliamentary system), a committee made up of a small number of parliamentary members appointed to deal with particular areas or issues

*Select or special committee (United States Congress)

*Select ...

on anatomy, whose report emphasised the importance of anatomical science and recommended that the bodies of paupers be given over for dissection. In response to the discovery in 1831 of a gang known as the London Burkers

The London Burkers were a group of body snatchers operating in London, England, who apparently modeled their activities on the notorious Burke and Hare murders. They came to prominence in 1831 for murdering victims to sell to anatomists, by luring ...

, who apparently modelled their activities on those of Burke and Hare, Parliament debated a bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Plac ...

submitted by Henry Warburton

Henry Warburton (12 November 1784 – 16 September 1858) was an English merchant and politician, and also an enthusiastic amateur scientist.

Elected as Member of Parliament for Bridport, Dorset, in the 1826 general election, he held the seat fo ...

, author of the Select Committee's report. Although it did not make body snatching illegal, the resulting Act of Parliament effectively put an end to the work of the resurrectionists by allowing anatomists access to the workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse'' ...

dead.

Legal background

Human cadavers have been dissected by physicians since at least the 3rd century BC, but throughout history, prevailing religious views on the desecration of corpses often meant that such work was performed in secrecy. The Christian church forbade human dissection until the 14th century, when the first recorded anatomisation of a cadaver took place inBologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nat ...

. Until then, anatomical research was limited to the dissection of animals. In Britain, human dissection was proscribed by law until 1506, when King James IV of Scotland

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauchi ...

gave royal patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

to the Barber-Surgeons of Edinburgh, allowing them to dissect the "bodies of certain executed criminals". England followed in 1540, when Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

gave patronage to the Company of Barber-Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS England) is an independent professional body and registered charity that promotes and advances standards of surgical care for patients, and regulates surgery and dentistry in England and Wales. The ...

, allowing them access to four executed felons each year ( Charles II later increased this to six felons each year). Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

granted the College of Physicians A college of physicians is a national or provincial organisation concerned with the practice of medicine.

{{Expand list, date=February 2011

Such institutions include:

* American College of Physicians

* Ceylon College of Physicians

* College of Phy ...

the right to anatomise four felons annually in 1564.

Several major hospitals and teaching centres were established in Britain during the 18th century, but with only a very few corpses legally available for dissection, these institutions suffered from severe shortages. Some local authorities had already attempted to alleviate the problem, with limited success; in 1694, Edinburgh allowed anatomists to dissect corpses "found dead in the streets, and the bodies of such as die violent deaths ... who shall have nobody to own them". Suicide victims were given over, as were infants who had died while being born and also the unclaimed bodies of abandoned children. But even though they were supported by the common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipresen ...

, anatomists occasionally found it difficult to collect what was granted to them. Fuelled by resentment of how readily the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

was used, and imbued with superstitious beliefs, crowds sometimes sought to keep the bodies of executed felons away from the authorities. Riots at execution sites were commonplace; worried about possible disorder, in 1749 the Sheriff of London

Two sheriffs are elected annually for the City of London by the Liverymen of the City livery company, livery companies. Today's sheriffs have only nominal duties, but the historical officeholders had important judicial responsibilities. They have ...

ignored the surgeons and gave the dead to their relatives.

These problems, together with a desire to enhance the deterrent effect of the death penalty, resulted in the passage of the Murder Act 1752

The Murder Act 1751 (25 Geo 2 c 37), sometimes referred to as the Murder Act 1752,Leon RadzinowiczA History of English Criminal Law and Its Administration from 1750 Macmillan Company. 1948. Volume 1. Page 801. was an Act of the Parliament of Gr ...

. It required that "every murderer shall, after execution, either be dissected or hung in chains". Dissection was generally viewed as "a fate worse than death"; giving judges the ability to substitute gibbeting

A gibbet is any instrument of public execution (including guillotine, executioner's block, impalement stake, hanging gallows, or related scaffold). Gibbeting is the use of a gallows-type structure from which the dead or dying bodies of crimi ...

with dissection was an attempt to invoke that horror. While the Act gave anatomists statutory

A statute is a formal written enactment of a legislative authority that governs the legal entities of a city, state, or country by way of consent. Typically, statutes command or prohibit something, or declare policy. Statutes are rules made by le ...

access to many more cadavers than were previously available, it proved insufficient. Attempting to bolster the supply, some surgeons offered money to pay the prison expenses and funeral clothing costs of condemned prisoners, while bribes were paid to officials present at the gallows, sometimes leading to an unfortunate situation in which corpses not legally given over for dissection were taken anyway.

Commodification

Documented cases of grave robbery for medical purposes can be found as far back as 1319. The 15th-centurypolymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

may have secretly dissected around 30 corpses, although their provenance remains unknown. In Britain, the practice appears to have been common early in the 17th century. For example, William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's epitaph reads "Good friend, for Jesus' sake forbear, To dig the dust enclosed here. Blessed be the man that spares these stones, And cursed be he that moves my bones" and in 1678, anatomists were suspected of being involved in the disappearance of an executed gypsy's body. Contracts issued in 1721 by the Edinburgh College of Surgeons include a clause directing students not to become involved in exhumation, suggesting, according to historian Ruth Richardson, that students had already done the exact opposite. Pupils accompanied professional body snatchers

Body snatching is the illicit removal of corpses from graves, morgues, and other burial sites. Body snatching is distinct from the act of grave robbery as grave robbing does not explicitly involve the removal of the corpse, but rather theft from ...

as observers, and were reported to have obtained and paid for their studies with human corpses, perhaps indicating that their tutors were complicit. The unauthorised removal of bodies from London graveyards became commonplace and by the 1720s, probably as a direct result of the lack of legally available bodies for anatomical research, fresh corpses had likely undergone commodification

Within a capitalist economic system, commodification is the transformation of things such as goods, services, ideas, nature, personal information, people or animals into objects of trade or commodities.For animals"United Nations Commodity Trad ...

.

Corpses and parts thereof were traded like any other merchandise: packed into suitable containers, salted and preserved, stored in cellars and quays

A wharf, quay (, also ), staith, or staithe is a structure on the shore of a harbour or on the bank of a river or canal where ships may dock to load and unload cargo or passengers. Such a structure includes one or more berths (mooring locatio ...

and transported in carts, waggons and boats. Encouraged by fierce competition, anatomy schools usually paid more promptly than their peers, who included individual surgeons, artists and others with an interest in human anatomy. As one body snatcher testified, "a man may make a good living at it, if he is a sober man, and acts with judgement, and supplies the schools".

In London, late 18th-century anatomists may have delegated their grave-robbing almost entirely to body snatchers, or, as they were commonly known, resurrectionists. A fifteen-strong gang of such men, exposed in Lambeth in 1795, supplied "eight surgeons of public repute, and a man who calls himself an Articulator". The report into their activities lists a price of two

In London, late 18th-century anatomists may have delegated their grave-robbing almost entirely to body snatchers, or, as they were commonly known, resurrectionists. A fifteen-strong gang of such men, exposed in Lambeth in 1795, supplied "eight surgeons of public repute, and a man who calls himself an Articulator". The report into their activities lists a price of two guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from t ...

and a crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

for a dead body, six shillings

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence or ...

for the first foot, and nine pence

A penny is a coin ( pennies) or a unit of currency (pl. pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (hence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. Presently, it is th ...

per inch "for all it measures more in length". These prices were by no means fixed; the black market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the se ...

value of corpses varied considerably. Giving evidence to the 1828 Select Committee on Anatomy, the surgeon Astley Cooper

Sir Astley Paston Cooper, 1st Baronet (23 August 176812 February 1841) was a British surgeon and anatomist, who made contributions to otology, vascular surgery, the anatomy and pathology of the mammary glands and testicles, and the pathology ...

testified that in 1828 the price for a corpse was about eight guineas, but also that he had paid anything from two to fourteen guineas previously; others claimed they had paid up to twenty guineas per corpse. Compared to the five shillings an East End

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have uni ...

silk weaver could earn each week, or the single guinea a manservant to a wealthy household was paid, these were considerable sums of money and body snatching was therefore a highly profitable business. Surgeons at the Royal College in Edinburgh complained that resurrectionists were profiteering, particularly when local shortages forced prices up. One surgeon told the Select Committee that he thought the body snatchers were manipulating the market for their own benefit, though no criticism was made of the "Anatomy Club", an attempt by anatomists to control the price of corpses for their benefit.

Prices also varied depending on what type of corpse was for sale. With greater opportunity for the study of musculature, males were preferable to females, while freak

A freak is a person who is physically deformed or transformed due to an extraordinary medical condition or body modification. This definition was first attested with this meaning in the 1880s as a shorter form of the phrase " freak of nature ...

s were more highly valued. The body of Charles Byrne, the so-called "Irish Giant", fetched about £500 when it was bought by John Hunter. Byrne's skeleton remains on display at the Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS England) is an independent professional body and registered charity that promotes and advances standards of surgical care for patients, and regulates surgery and dentistry in England and Wales. The ...

. Children's bodies were also traded, as "big smalls", "smalls" or foetuses. Parts of corpses, such as a scalp with long hair attached, or good quality teeth, also fetched good prices—not because they held any intrinsic value to the anatomist, but rather because they were used to refurbish the living.

With no reliable figures for the number of dissections that took place in 18th-century Britain, the true scale of body snatching can only be estimated. Richardson suggests that nationally, several thousand bodies were robbed each year. The 1828 Select Committee reported that in 1826, 592 bodies were dissected by 701 students. In 1831, only 52 of 1,601 death penalties handed down were enacted, a number far too small to meet demand. Since corpses were not viewed as property and could neither be owned nor stolen, body snatching remained quasi-legal, the crime being committed against the grave rather than the body. On the rare occasions they were caught, resurrectionists might have received a public whipping, or a sentence for crimes against public mores

Mores (, sometimes ; , plural form of singular , meaning "manner, custom, usage, or habit") are social norms that are widely observed within a particular society or culture. Mores determine what is considered morally acceptable or unacceptable ...

, but generally the practice was treated by the authorities as an open secret and ignored. A notable exception occurred in Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

in 1827, with the capture of three resurrectionists. At a time when thieves were regularly transported

''Transported'' is an Australian convict melodrama film directed by W. J. Lincoln. It is considered a lost film.

Plot

In England, Jessie Grey is about to marry Leonard Lincoln but the evil Harold Hawk tries to force her to marry him and she w ...

for theft, two of the body snatchers were discharged and the third, sent to London for trial, was imprisoned for only six months. Resurrectionists were also aided by the corpse's anatomisation; since the process also destroyed the evidence, a successful prosecution was unlikely.

Resurrection

Method

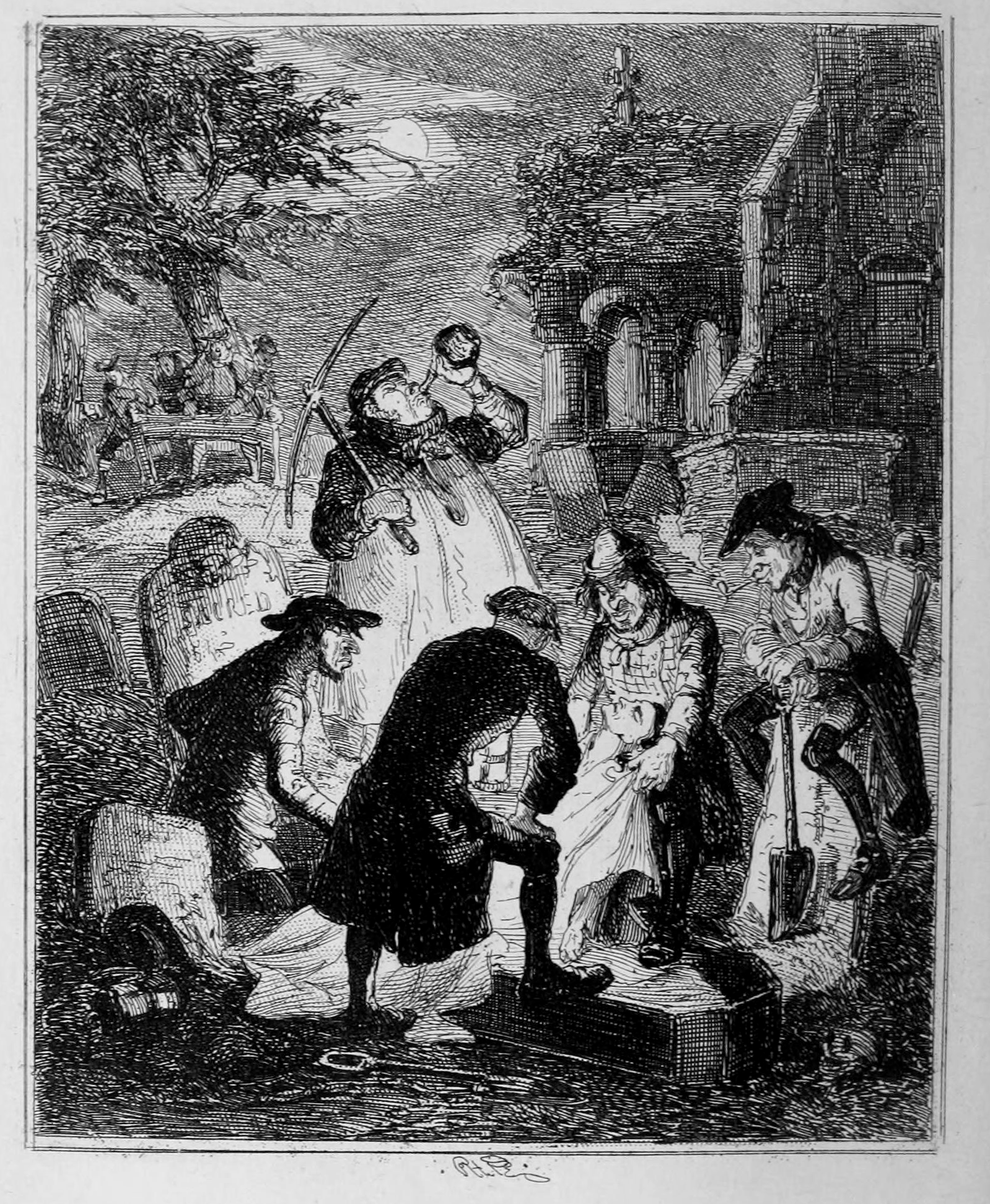

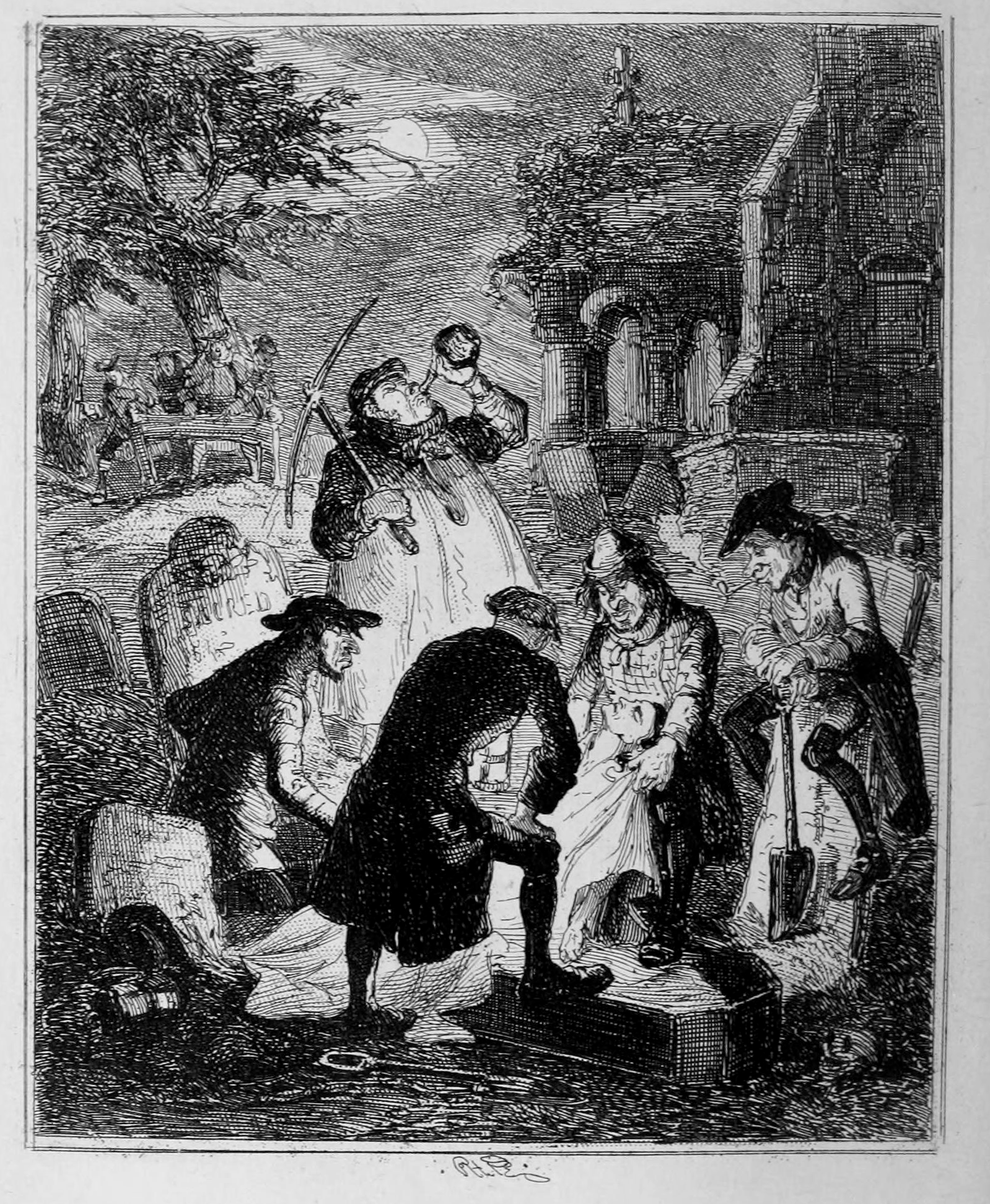

Resurrectionists usually found corpses through a network of informers. Sextons, gravediggers, undertakers, local officials; each connived to take a cut of the proceeds. Working mostly in small gangs at night with a "dark lanthorn", their ''

Resurrectionists usually found corpses through a network of informers. Sextons, gravediggers, undertakers, local officials; each connived to take a cut of the proceeds. Working mostly in small gangs at night with a "dark lanthorn", their ''modus operandi

A ''modus operandi'' (often shortened to M.O.) is someone's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also more generally. It is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as "mode (or manner) of op ...

'' was to dig a hole—sometimes using a quieter, wooden spade—down to one end of the coffin. To disguise this activity, the spoil was sometimes thrown onto a piece of canvas at the side of the grave. A sound-deadening sack was placed over the lid, which was then lifted. The weight of soil on the remainder of the lid snapped the wood, enabling the robbers to hoist the body out. The corpse was then stripped of its clothing, tied up, and placed into a sack. The entire process could be completed within 30 minutes. Moving the corpse of a pauper was less troublesome, as their bodies were often kept in mass grave

A mass grave is a grave containing multiple human corpses, which may or may not be identified prior to burial. The United Nations has defined a criminal mass grave as a burial site containing three or more victims of execution, although an exact ...

s, left open to the environment until filled—which often took weeks.

If caught in the act, body snatchers could find themselves at the mercy of the local population. A violent confrontation took place in a Dublin churchyard in 1828, when a party of mourners confronted a group of resurrectionists. The would-be body snatchers withdrew, only to return several hours later with more men. The mourners had also added to their number, and both groups had brought firearms. A "volley of bullets, slugs, and swan-shot from the resurrectionists" prompted a "discharge of fire-arms from the defenders". Close-quarters fighting included the use of pick axes, until the resurrectionists retreated. In the same city, a man caught removing a corpse from a graveyard in Hollywood was shot and killed in 1832. In the same year, three men were apprehended while transporting the bodies of two elderly men, near Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, within the London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century to the late 19th it was home to Deptford Dock ...

in London. As rumours spread that the two corpses were murder victims, a large crowd assembled outside the station house. When the suspects were brought out to be transported to the local magistrates, the approximately 40-strong force of police officers found it difficult to "prevent their prisoners being sacrificed by the indignant multitude, which was most anxious to inflict such punishment upon them as it thought they deserved."

Gangs

As many as seven gangs of resurrectionists may have been at work in 1831. The 1828 Select Committee on Anatomy believed that there were about 200 London resurrectionists, most of them working part-time. The London Borough Gang, which operated from about 1802 to 1825, at its peak consisted of at least six men, led first by a former hospital porter named Ben Crouch, and later by a man called Patrick Murphy. Under the protection of Astley Cooper, Crouch's gang supplied some of London's biggest anatomical schools, but relations were not always amicable. In 1816 the gang cut off supplies to the St Thomas Hospital School, demanding an increase of two guineas per corpse. When the school responded by using freelancers, members of the gang burst into the dissecting rooms, threatened the students and attacked the corpses. The police were called, but worried about adverse publicity, the school paid their attackers' bail and opened negotiations. The gang also attempted to put rivals out of business, sometimes by desecrating a graveyard (thereby rendering it unsafe to rob graves from for weeks thereafter) and other times by reporting freelance resurrectionists to the police, recruiting them once freed from prison. Joshua Naples, who wrote ''The Diary of a Resurrectionist'', a list of his activities from 1811–1812, was one such individual. Among entries detailing the graveyards he plundered, the institutions he delivered to, how much he was paid and his drunkenness, Naples diary mentions his gang's inability to work under a full Moon, being unable to sell a body deemed "putrid", and leaving a body thought to be infected with

As many as seven gangs of resurrectionists may have been at work in 1831. The 1828 Select Committee on Anatomy believed that there were about 200 London resurrectionists, most of them working part-time. The London Borough Gang, which operated from about 1802 to 1825, at its peak consisted of at least six men, led first by a former hospital porter named Ben Crouch, and later by a man called Patrick Murphy. Under the protection of Astley Cooper, Crouch's gang supplied some of London's biggest anatomical schools, but relations were not always amicable. In 1816 the gang cut off supplies to the St Thomas Hospital School, demanding an increase of two guineas per corpse. When the school responded by using freelancers, members of the gang burst into the dissecting rooms, threatened the students and attacked the corpses. The police were called, but worried about adverse publicity, the school paid their attackers' bail and opened negotiations. The gang also attempted to put rivals out of business, sometimes by desecrating a graveyard (thereby rendering it unsafe to rob graves from for weeks thereafter) and other times by reporting freelance resurrectionists to the police, recruiting them once freed from prison. Joshua Naples, who wrote ''The Diary of a Resurrectionist'', a list of his activities from 1811–1812, was one such individual. Among entries detailing the graveyards he plundered, the institutions he delivered to, how much he was paid and his drunkenness, Naples diary mentions his gang's inability to work under a full Moon, being unable to sell a body deemed "putrid", and leaving a body thought to be infected with smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

.

Violent mobs were not the only problems body snatchers faced. Naples also wrote of how he met "patrols" and how "dogs flew at us", references to some of the measures taken to secure graves against his ilk. The aristocracy and very rich placed their dead in triple coffins, vaults and private chapels, sometimes guarded by servants. For the less wealthy, double coffins were available, buried on private land in deep graves. More basic defences included the placing of heavy weights over the coffin, or simply filling the grave with stones rather than soil. Such deterrents were sometimes deployed in vain; at least one London graveyard was owned by an anatomist who, it was reported, "obtained a famous supply f cadaversnbsp;... and he could charge pretty handsomely for burying a body there, and afterwards get from his pupils from eight to twelve guineas for taking it up again!" Ever more elaborate creations included ''The Patent Coffin'', an iron contraption with concealed springs to prevent any levering of its lid. Corpses were sometimes secured inside their caskets by iron straps, while other designs used special screws to reinforce metal bands placed around the coffin. In Scotland, iron cages called mortsafes either encased buried coffins, or were set in a concrete foundation and covered the whole grave. Some covered more than one coffin, while others took the form of iron lattices fixed beneath large stone slabs, buried with the coffin. They may not have been secure enough; as one 20th-century writer observed, an empty coffin found beneath a buried mortsafe in Aberlour

Aberlour ( gd, Obar Lobhair) is a village in Moray, Scotland, south of Elgin on the road to Grantown. The Lour burn is a tributary of the River Spey, and it and the surrounding parish are both named Aberlour, but the name is more commonly used ...

had probably been "opened during the night succeeding the funeral, and carefully closed again, so that the disturbance of the soil had escaped notice or had been attributed to the original burial."

Other methods

Occasionally, resurrectionists paid women to pose as grieving relatives, so that they might claim a body from a workhouse. Some parishes did little to stop this practice, as it reduced their funeral expenditure. Bodies were also taken fromdead house

A dead house, deadhouse or mort house, is a structure used for the temporary storage of a human corpse before burial or transportation, usually located within or near a cemetery. Such edifices were more common before the mid-20th century in area ...

s; Astley Cooper's servant was once forced to return three bodies, worth £34 2s, to a dead house in Newington parish. Bribes were also paid, usually to servants of recently deceased employers then lying in state, although this method carried its own risks as corpses were often placed on public display before they were buried. Some were taken from private homes; in 1831 ''The Times'' reported that "a party of resurrectionists" burst into a house in Bow Lane and took the body of an elderly woman, who was being waked' by her friends and neighbours". The thieves apparently "acted with the most revolting indecency, dragging the corpse in its death clothes after them through the mud in the street". Bodies were even removed—with no legal authority—from prisons and naval and military hospitals.

While some surgeons eschewed human cadavers in favour of facsimiles, plaster casts, wax models and animals, bodies were also taken from hospital burial grounds. Recent excavations at the Royal London Hospital

The Royal London Hospital is a large teaching hospital in Whitechapel in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is part of Barts Health NHS Trust. It provides district general hospital services for the City of London and Tower Hamlets and spe ...

appear to support claims made almost 200 years earlier that the hospital's school was "entirely supplied by subjects, which have been their own patients".

Dissection and anatomy

Public view

Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and south (modern Ox ...

to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

, reduced the likelihood of public interference and strengthened the authorities' hold over felons. However, society's view of dissection remained unequivocal; most preferred gibbeting to the laying open of a corpse. Martin Gray, sentenced to death in 1721 for returning early from transportation, was "greatly frighted, least his Body should be cut, and torn, and mangled after Death, and had sent his Wife to his Uncle to obtain some money to prevent it." Vincent Davis, convicted in 1725 of murdering his wife, said he would rather be "hang'd in Chains" than "anatomiz'd", and to that effect had "sent many Letters to all his former Friends and Acquaintance to form a Company, and prevent the Surgeons in their Designs upon his Body". There are cases of criminals who survived the short drop

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

, but dissecting the body removed any hope of escape from death's embrace. Anatomists were popularly thought to be interested in dissection only as enactors of the law, a relationship first established by kings James IV and Henry VIII. Thomas Wakley, editor of ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

The journal publishes original research articles, ...

'', wrote that this lowered "the character of the profession in the public mind." It was also thought that the anatomists' work made the body's owner unrecognisable in the afterlife. Therefore, while less hated than the resurrectionists they employed, anatomists remained at risk of attack. Relatives of a man executed in 1820 killed one anatomist and shot another in the face, while in 1831, following the discovery of buried human flesh and three dissected bodies, a mob burnt down an anatomy theatre in Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

. The theatre's proprietor, Andrew Moir, escaped through a window, while two of his students were chased through the streets.

Some aspects of the popular view of dissection were exemplified by the final panel of William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like s ...

's ''The Four Stages of Cruelty

''The Four Stages of Cruelty'' is a series of four printed engravings published by English artist William Hogarth in 1751. Each print depicts a different stage in the life of the fictional Tom Nero.

Beginning with the torture of a dog as a ch ...

'', a series of engravings that depict a felon's journey to the anatomical theatre. The chief surgeon ( John Freke) appears as a magistrate, watching over the examination of the murderer Tom Nero's body by the Company of Surgeons. According to author Fiona Haslam, the scene reflects a popular view that surgeons were "on the whole, disreputable, insensitive to human suffering and prone to victimis ngpeople in the same way that criminals victimised their prey." Another popular belief alluded to by Hogarth was that surgeons were so ignorant of the respect due to their subjects, that they allowed the remains to become offal

Offal (), also called variety meats, pluck or organ meats, is the organs of a butchered animal. The word does not refer to a particular list of edible organs, which varies by culture and region, but usually excludes muscle. Offal may also refe ...

. In reality, the rough treatment exacted by body snatchers on corpses continued on the premises they delivered to. Joshua Brookes

Joshua Brookes (24 November 1761 – 10 January 1833) was a British anatomist and naturalist.

Early life

Brookes studied under William Hunter, William Hewson, Andrew Marshall, and John Sheldon, in London. He then attended the practice of ...

once admitted that he had kicked a corpse in a sack down a flight of stairs, while Robert Christison

Sir Robert Christison, 1st Baronet, (18 July 1797 – 27 January 1882) was a Scottish toxicologist and physician who served as president of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (1838–40 and 1846-8) and as president of the British ...

complained of the "shocking indecency without any qualifying wit" demonstrated by a male lecturer who dissected a woman. Pranks were also common; a London student who jokingly dropped an amputated leg down a household chimney, into a housewife's stewpot, caused a riot.

Anatomy Act 1832

In March 1828, in

In March 1828, in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

, three defendants charged with conspiracy and unlawfully procuring and receiving a corpse buried in Warrington

Warrington () is a town and unparished area in the borough of the same name in the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England, on the banks of the River Mersey. It is east of Liverpool, and west of Manchester. The population in 2019 was estimat ...

were acquitted, while the remaining two were found guilty of possession. The presiding judge's comment, that "the disinterment of bodies for dissection was an offence liable to punishment", prompted Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

to establish the 1828 Select Committee on Anatomy. The committee took evidence from 40 witnesses: 25 members of the medical profession, 12 public servants and 3 resurrectionists, who remained anonymous. Discussed were the importance of anatomy, the supply of subjects for dissection and the relationship between anatomists and resurrectionists. The committee concluded that dissection was essential to the study of human anatomy and recommended that anatomists be allowed to appropriate the bodies of paupers.

The first bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Plac ...

was presented to Parliament in 1829 by Henry Warburton

Henry Warburton (12 November 1784 – 16 September 1858) was an English merchant and politician, and also an enthusiastic amateur scientist.

Elected as Member of Parliament for Bridport, Dorset, in the 1826 general election, he held the seat fo ...

, author of the Select Committee's report. Following a spirited defence of the poor by peers in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, it was withdrawn, but almost two years later Warburton introduced a second bill, shortly after the execution of John Bishop and Thomas Williams. The London Burkers

The London Burkers were a group of body snatchers operating in London, England, who apparently modeled their activities on the notorious Burke and Hare murders. They came to prominence in 1831 for murdering victims to sell to anatomists, by luring ...

, as the two men were known, were inspired by a series of murders committed by William Burke and William Hare, two Irishmen who sold their victims' bodies to Robert Knox

Robert Knox (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in the Burke and Hare murders. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox eventually partnered with anatomist and former teache ...

, a Scottish surgeon. Even though Burke and Hare never robbed graves, their case lowered the public's view of resurrectionists from desecraters to potential murderers. The resulting wave of social anxiety helped speed Warburton's bill through Parliament, and despite much public opprobrium, with little Parliamentary opposition the Anatomy Act 1832

The Anatomy Act 1832 (2 & 3 Will. IV c.75) is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that gave free licence to doctors, teachers of anatomy and bona fide medical students to dissect donated bodies. It was enacted in response to public revu ...

became law on 1 August 1832. It abolished that part of the 1752 Act that allowed murderers to be dissected, ending the centuries-old tradition of anatomising felons, although it neither discouraged nor prohibited body snatching, or the sale of corpses (whose legal status remained uncertain). Another clause allowed a person's body to be given up for "anatomical examination", provided that the person concerned had not objected. As the poor were often barely literate and therefore unable to leave written directions in the event of their death, this meant that masters of charitable institutions such as workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse'' ...

s decided who went to the anatomist's table. A stipulation that witnesses could intervene was also abused, as such witnesses might be fellow inmates who were powerless to object, or workhouse staff who stood to gain money through wilful ignorance.

Despite the passage of the Anatomy Act, resurrection remained commonplace, the supply of unclaimed paupers' bodies at first proving inadequate to fulfil the demand. Reports of body snatching persisted for some years; in 1838, Poor Law Commissioners reported on two dead resurrectionists who had contracted an illness from a putrid corpse they had unearthed. By 1844, the trade mostly no longer existed.An isolated case was noted in Sheffield, Wardsend Cemetery in

1862

See also

* Anatomy murder *History of anatomy

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of sacrifice, sacrificial victims to the sophisticated analyses of the body performed by modern anatomists and scientists. Written descriptions of human organs and parts can be traced ...

* The Fortune of War Public House

The Fortune of War was an ancient public house in Smithfield, London. It was located on a corner originally known as 'Pie Corner', today at the junction of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane where the Golden Boy of Pye Corner resides, the name derivin ...

, a pub famous for its role as a meeting place where resurrectionists would sell cadavers to surgeons

* Jerry Cruncher

Jeremiah "Jerry" Cruncher is a fictional character in Charles Dickens' 1859 novel ''A Tale of Two Cities''.

Overview

Jeremiah "Jerry" Cruncher is employed as a ''porter'' for Tellson's Bank of London. He earns extra money as a Resurrectionists ...

, a resurrectionist featured in Charles Dickens' novel ''A Tale of Two Cities

''A Tale of Two Cities'' is a historical novel published in 1859 by Charles Dickens, set in London and Paris before and during the French Revolution. The novel tells the story of the French Doctor Manette, his 18-year-long imprisonment in the ...

''

References

Footnotes Notes Bibliography * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* For the 1828 Select Committee report on Anatomy, see * For a study of the theft and dissection of the body parts of famous people, seeExternal links

* {{Cite web , last = Chaplin , first = Simon David John , title = John Hunter and the 'museum oeconomy', 1750–1800 , url = http://library.wellcome.ac.uk/content/documents/john-hunter-and-the-museum-oeconomy , publisher = library.wellcome.ac.uk , date = May 2009 , mode=cs2 Persons involved with death and dying Body snatching Burials Medical education in the United Kingdom